It’s all About Drains

The title is not very appetising perhaps, but water management is an increasingly important part of Wilderness Wood environmental management.

French drain inserted (right) addresses the overflow risk provided by an open drain (left)

This week the Conservation Volunteers (every Wednesday 10am) were tasked with filling the French Drain around the new workshop with ‘beach’ material (larger than pea shingle). A French Drain is a trench containing a pipe with holes in it, surrounded by pebbles (French is the name of the American who invented this kind of drain, not the country). Water drains off the land (or the roof of the workshop in this case) and percolates down through the pebbles before finding its way into the holed pipe to be conducted into an adjacent watercourse.

The volunteers must have shifted a couple of tons of the stuff, completely burying the holed pipe. Amazing what a dozen people can shift in just 30 minutes.

By way of recovery all had a sit down and a drink of water before disappearing off to the Christmas Tree Field for their next task. In the meantime I went to Bat Park to continue my drain theme. Last week I explained how I hoped to encourage excess water to run along a new trench dug alongside the hedge shrubs liberated from bracken and bramble.

Trench created to carry water from the Bat Park grassland and supply it to these young hedge shrubs

Their was evidence of recent rainfall having entered the trench but it was obvious greater depth was required. 10 minutes of digging may have helped, but you can just have so much of drains. So I went for a scout around for significant signs of wildlife. This included Pixie Cup lichens, a late flowering Ragwort plant, Tormentil and Common Heather seed heads.

The Pixie Cups should turn red shortly and look like something out of the Rupert Bear Annuals my gran used to buy for us to read. The Ragwort is significant because I only recorded it for the first time at Bat Park in 2023. This common weed of pastures has taken about 5 years to colonise our acid lowland grassland and its a sign that things are progressing. Tormentil is not in flower but it is becoming ever-more common, creeping through the acidic soil of our grassland. The heather is a welcome sight up to a point, but we are now in danger of the anticipated acid lowland grassland becoming a lowland heath as its seeds spread around. To arrest its transition to heathland we either need to put sheep on it, or mow it down to size. The latter is the more likely solution.

Ragwort, Pixie Cup Lichen, Tormentil and Common Heather have colonised Bat Park

With an hour to spare before lunch, I pop down to the wet woodland to admire the rerouted Wilderness Stream spreading its life-giving waters across the woodland floor (instead of being allowed to form a single channel through the wood). The mantra has to be “provide the water and they will come” (‘they’ being wet woodland plants). As with Bat Park (and unlike most gardens) this is not going to be an instant colonisation - patience is required when restoring a habitat, but every new arrival is the more exciting because of this.

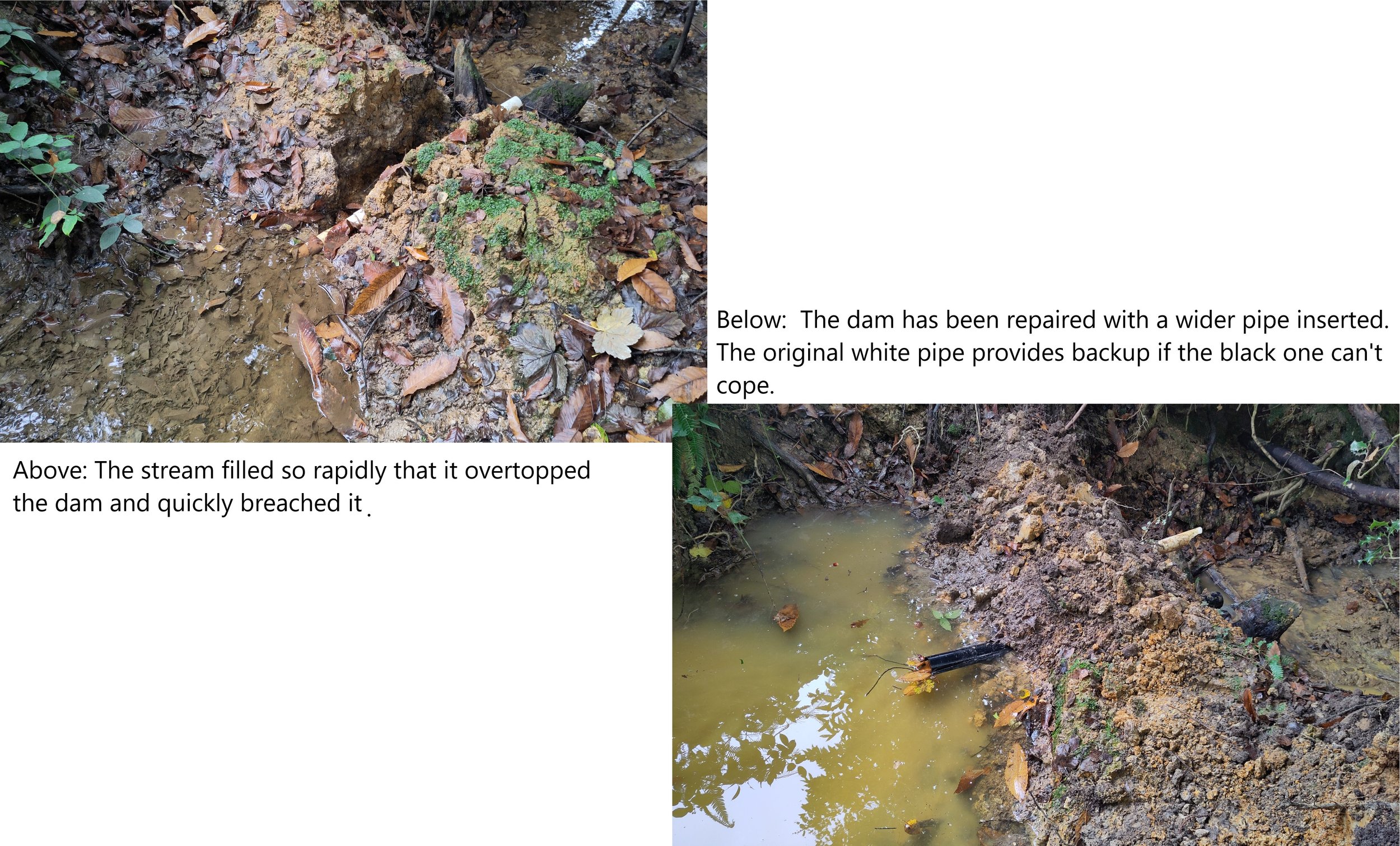

My main focus here is repair of the dam I put across the old channel of the Wilderness Stream. Only a relatively small amount of water drains down it now, so it lends itself to having a series of in-line ponds held back by earth dams and fitted with an overflow pipe. Recent heavy rains saw the old stream channel wash away the overflow pipe so I’ve returned to fit a new, bigger pipe and restore the dam. Yes more drain related activity!

.Wet woodland in-line pond repair

By 12.30 the job is done and I am covered top-to-toe in Wealden mud. However, I have enough time to sit for five minutes and admire the fruits of my labours before the uphill trudge back to The Barn to claim my much needed lunch.

David Horne

You can look back at “A Year in the Wilderness” by scrolling back through the posts on this blog. Alternatively you can buy a copy of “A Year in the Wilderness by David Horne” £8 from Amazon

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Year-Wilderness-Wildlife-Conservation-2023-2024/dp/B0D12RK4WF