Bat Park in Winter

5 December 2023

I was not looking forward to today's weather. It chucked it down on Sunday and the forecast

was no different for today. But such are the vagaries of the English weather that when I arrive it

is mercifully dry. Cold maybe, an ever-present threat of drizzle in the air perhaps, but at least I

can start in the dry and run for cover if needed.

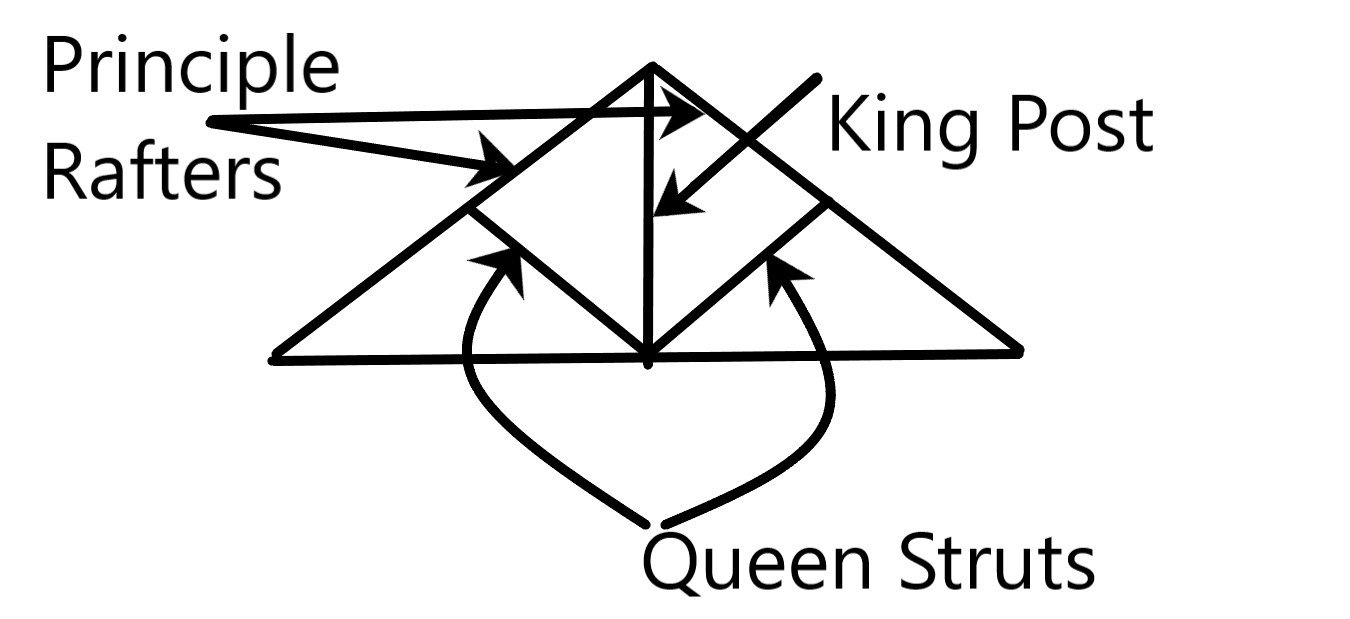

As ever, I have to check on progress on the man-made aspects of Wilderness Wood, so I pop over to survey the new workshops where Daryl explains the nature of the building process. “We had to make up 18 roof trusses using Wilderness Wood chestnut trees. Each frame took about two and a half days to build.”

The new workshops take shape. A strange amalgam of reycled shipping containers and hand built sweet chestnut roof trusses.

The use of such large lumps of timber may be a case of over-engineering, since the roof will only be clad in corrugated tin, but the aesthetic is beyond price. At least the roof is future-proof should someone want to clad it in 10mm steel plate and a metre of reinforced concrete. A sort of modern day Anderson Shelter or nuclear bunker, should it be needed.

The use of wood is perhaps counter intuitive to some, since it involves cutting down trees. However, trees, just like any farm crop, undergo planting, growing and harvesting, although the life cycle is somewhat more elongated. The building material utilised is carbon neutral, especially since it is grown on site, so no transportation carbon involved. Further, any carbon taken up by the living tree remains in the timber, potentially for centuries. Compare this to concrete buildings which involve enormous amounts of carbon dioxide being released during manufacture and you quickly realise timber framing has an important place in sustainable building.

Wooden roof truss morphology. 10cm x 5cm (approx) timbers all connected by mortice and tenon joints. A thing of beauty.

I leave Daryl to his recycled 21st Century shipping containers, topped off with mediaeval timber framing and start foraging. Not for anything edible, but for bits of chicken wire left over from previous jobs. Nothing need be wasted, with the leftovers earmarked for cutting into sections to keep Peter Rabbit out of Bat Park, at least until the acid lowland grassland there has reached it's optimum height – perhaps half a metre? We can let the bunnies back in to mow it in a couple of years time, perhaps as a Christmas treat each December. At least it would save on the electricity using the strimmer alternative.

Proud of my sustainability credentials and with my foraged chicken wire under my arm I make my way over towards Bat Park. On the way I pass Bea entertaining small children with a song about dinosaurs. A little insensative but I try not to take it personally, although the chorus “great big body and tiny little head” is a gross distortion of fact!

Arriving at Bat Park I check things over. The French drains are taking excess water away, whilst the grassland is stubbornly short at perhaps 5cm, thanks to rabbit grazing, except where the chicken wire enclosures exclude them. Here the leaves are maybe 10cms tall and the flower stalks 30 cm. So well short of the 50cm optimum.

This short turf is the ungrazed grassland at Bat Park, beyond it is probably less than 5cm tall.

Still, after nearly 6 years of 'cultivation' we have an interesting sward of grass with a few wild flowers thrown in for good measure. In fact rabbit-grazed sward may well become an endangered habitat one day. I know that wild rabbit grazing is seen as beneficial in the Norfolk Brecklands, producing a sward considered comparable to that once produced by large grazing animals (megafauna) in the area many thousands of years ago. Personally I find European Bison more interesting, but beggars can't be choosers!

A closer look at the different species of wildflowers mixed in with the grasses gives great cause for hope. These however are still very small and it will be perhaps a few years before Bat Park becomes the sea of colour I once promised Dan and Emily.

Clockwise from top left: creeping buttercup, tormentil, common heather, ox-eye daisy

One area of Bat Park which has progressed well over the last 6 years is the heathland area. This is marked on old vegetation maps but hardly existed at all back in 2018. I'm told a serious fire destroyed much of it, leaving just sterile blackened soil. Common heather now dominates much of this area, giving a riot of purple in August. However, bracken fronds tend to hide this from view until December cold has caused the bracken to abandon its aerial shoots until late spring. Now the developing heather becomes apparent up near the top double gate, close to the conifer plantation and where we planted small plugs in lines across the bare ground.

Heather regeneration at Bat Park. Top two photos - natural regeneration, bottom left -planted plugs, bottom right - mature heather produces masses of seed for natural regeneration.

But I have work to do and set about cutting the scavenged chicken wire with a strong pair of gardening scissors. The wire is cut into 20cm wide strips and by the time I've finished I have about 13 metres of what I hope will be rabbit-proof skirt around the bottom of the deer fence. There is a long way to go before Bat Park is rabbit free, but it is probably 20% done.

Cutting chicken wire with scissor is not a bloodless activity

The 12.30 dinner bell goes, just like it did at school back in the 1960s and my response is unchanged by 50 or 60 years since then – I scurry up to the barn before all the other hungry home team mouths have eaten it all.

Follow my exploration of the England and Wales Coast Path at www.leggingroundbritain.com