A Hydrology Field Excursion

Wilderness Diary Tuesday 07/11/23

I'm meeting up with Leilani, one of the regular volunteer helpers at Wilderness Wood. Leilani has a grand-daughter (Carly) who is studying for her Geography GCSE exam next May. She is home educated by Leilani.

After discussion of some sample papers, Leilani shows me a diagram from a sample exam question. This diagram of the hydrological cycle seems to suggest that rain falls on mountains, runs-off down rivers into the sea and then returns by way of evaporation from the sea to the clouds, which deposit their water in the form of rain onto the mountains. It is a widely used diagram, but I could well imagine many a child assuming from this that it only rains in the mountains. I know from long experience that it rains everywhere in the UK – mountain or otherwise. I do however accept that it rains much more in mountain and hill areas.

A simplified Hydrological Cycle diagram

I decide it would be useful if I took her on a tour of the woods in order to explain the movement of water within the Hydrological Cycle in greater detail. Reader, you are welcome to join us.

We start not only at the highest part of the wood, but at its newest surface – the floor of the new workshop that has been under construction for the last couple of weeks.

The new workshops - a model of urban surface run-off

The highest point in the wood is important since most diagrams you will find in books suggest that the water cycle begins here. This is not entirely true, since being a cycle it has neither a start nor an end – it is a continuous process. But at least you could argue that this is where river systems begin before they flow down to the sea. This too is a little misleading since most of the water entering a river channel does not do so at the start of each stream that feeds into it, but continuously along its length from the bedrock, soil and springs adjacent to it. Beware of over-simplification.

Nonetheless we are going to follow the progress of the Wilderness Stream through the wood to the point where it leaves to join the Tickerage Stream, its waters then continue into the River Uck and finally into the River Ouse, before entering the sea at Newhaven.

Before following our natural basin hydrological cycle (the bit that just covers water movement within a river basin and not the sea or the atmosphere) we pause to consider the impact of Dan's new workshop floor. Rain falling onto this floor (currently not covered by a soon to be erected roof) runs immediately off the concrete and into drains which feed it into the top end of the Wilderness Stream.

Heavy rainfall has run-off into this drainage ditch, taking sediment into the Wilderness Stream

You will see from this photograph that yesterdays rainfall has already disappeared, such is the immediacy of water falling onto concrete surfaces. Once the roof is on it will probably be even more immediate. The new workshop is a good metaphor for what happens in every urban area in the UK (and probably worldwide). Roads, buildings, school playgrounds, car parks and factory roofs all act as impermeable bedrock, preventing any water soaking into the ground, from which drains quickly remove it into natural river channels.

It should therefore come as no surprise that this water quickly fills these river channels, especially further downstream where so much of it arrives so quickly that the river bursts its banks, thereby flooding adjacent land. Somewhat ironically this land is often occupied by roads, buildings, school playgrounds, car parks etc. People living in towns and cities next to lowland rivers therefore regularly suffer from flood water in the UK winter time. It should be of no surprise were a question on this to come up in Carly's GCSE Geography exam next year. Climate change appears to be making the seasonal nature of rainfall increasingly extreme in the UK – drier summers and wetter winters.

The Natural Hydrological Cycle

But let's continue with the natural basin hydrological cycle. I pause briefly to point out the stand of trees here at the top of the wood. Most British hillsides would at one time have been similarly cloaked in trees. One exception might have been the relatively flat areas close to the tops of ranges such as The Pennines, The Lake District, Scottish Highlands, Dartmoor etc. Here it is possible that huge areas of peat bog may have once prevailed.

Sadly the peat bogs in mountain areas and their lowland cousins are under threat. The former largely due to 19th and 20th Century industrial pollution killing the peat forming plants such as sphagnum moss. Instead of these vast tracts of moss covered land holding rainwater and releasing it into streams slowly, it now tumbles off the hills in deeply eroded channels and down to the lowland rivers as a flash flood to engulf adjacent settlements. York and Tewkesbury come immediately to mind, as do the nearby East Sussex towns of Uckfield and Lewes which saw flooding in 2000.

Many of the once forested areas of our hillsides have been turned into heather moorland for sheep farming and the hunting of deer and grouse. Trees play an important part in the hydrological cycle, slowing the movement of water as it makes its way towards stream and river channels.

Sadly much of the lowland peat areas of the UK - The Somerset Levels, The Fens, South Yorkshire, have lost their peat forming plants due to the extraction of peat for the horticultural industry. These too could serve as flood water storage opportunities.

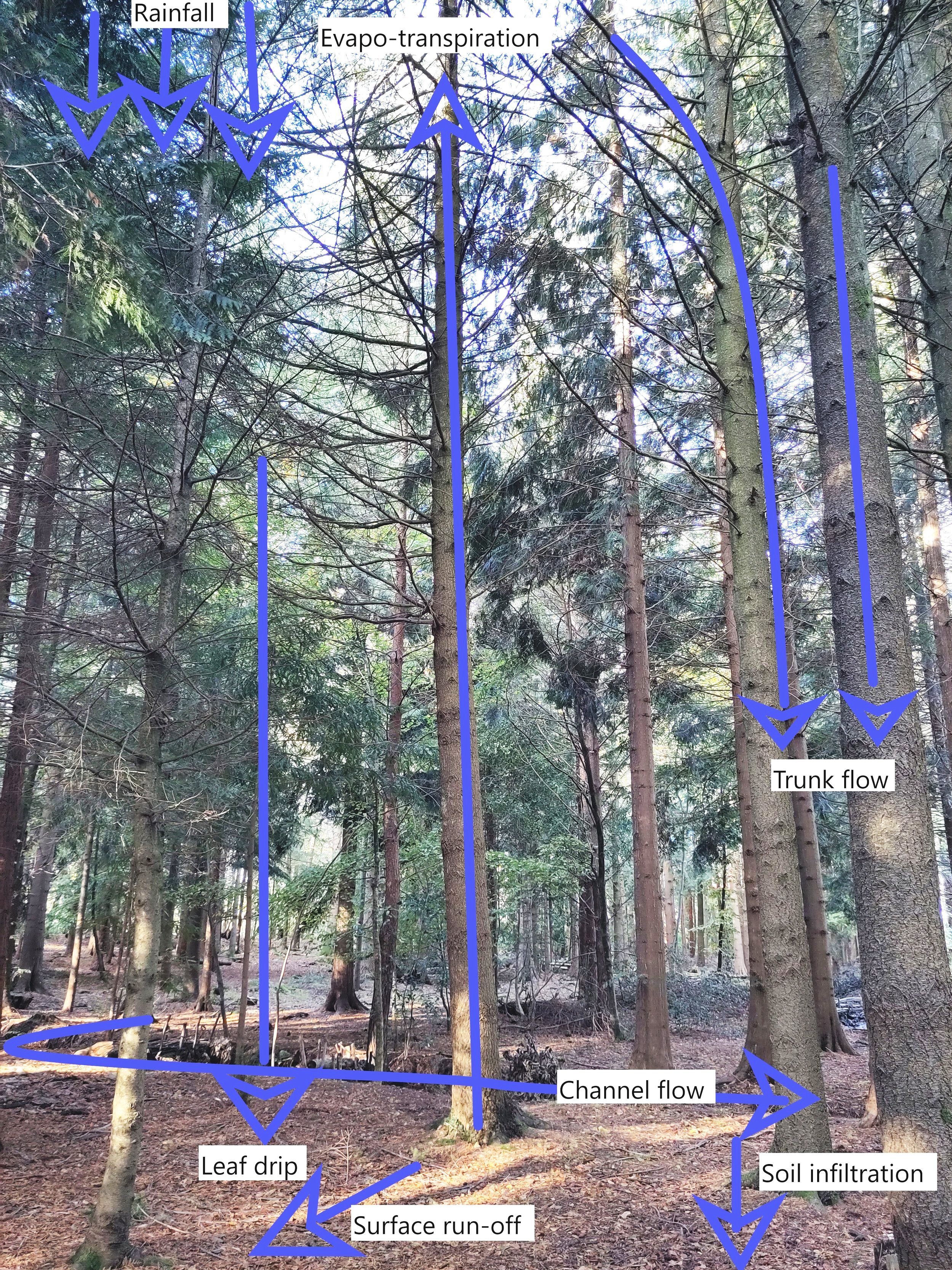

Upper Conifer Plantation, Wilderness Wood showing water movement

When rain falls onto tree covered land the tree leaf surfaces hold significant amounts of water, which is a slightly 'sticky' substance. Water then drips off the leaves or runs slowly down tree branches and the trunk to the soil beneath. Woodland soils are generally very deep and can soak up large amounts of rainwater, as do the roots of trees which take it through the tree to return the water to the atmosphere through evapo-transpiration. Any excess rainwater now infiltrates into the bedrock where it slowly percolates downhill into the stream or river channel.

In the High Weald the bedrock is so impermeable that much of the rainwater actually travels overland as surface run-off. This is a natural process in the High Weald, unlike in cities where the problem is man-made – like our concrete workshop floor.

At one time river flow would have been much slower than it is today, due to large amounts of dead tree material clogging up the channel. Modern day farming and forestry is much more efficient and tidy, clearing this material away. Even the European Beaver played its part in the past, building dams which held back the water. Alas man hunted the beaver to extinction in the UK. Many rivers have been straightened in their lower courses in an attempt to control them. All this has achieved is to speed the river flow, especially during periods of flash flooding. Oops! It seems man has to take a long look in the mirror!

Passing through the woods there is little to see or hear from animal life, but clumps of sulphur tuft, and fly agaric remind us that nature is still busy operating below ground at least. A small path runs off from the cross ride next to the Christmas Tree Field. We follow it a short way, where I reacquaint myself with one of the first jobs I did here 9 years ago – a set of wooden 'stepping stones' in the path.

Wooden stepping stones across a marshy area of the path

They were placed because a spring arises here, flooding the path whenever it rains. In fact a number of springs rise here, probably induced by a change in bedrock. This part of the wood is very wet, evidenced by lots of sphagnum moss growing on the woodland floor. You may recall that this is the stuff that created all those peat bogs in the UK. A good environment for sequestering carbon as well as storing excess water.

This blog constantly bangs on about leaky dams, but that is because they are an important mitigation against flooding. Leilani and I pause briefly to examine the one at the top of Hemlock Valley. A significant amount of water is held back, along with over half a meter depth of sediment. This sediment is here because rivers erode the land and transport it as they flow downstream. This accumulation of eroded material is in fact evidence that our leaky dam is doing its job. Slowing the water down, it looses the power to carry sediment further and has deposited it here over the last 2 or 3 years.

Downstream of Hemlock Valley our new ponds are also trapping water and slowing it further. We pause to admire the beauty that a pond can bring to a place. Lots of plants have sprung up over the last 12 months since it was dug. A movement in the clear water catches my eye, a full grown frog kicks its long legs and is quickly out of sight. It probably hatched from spawn in this very pond earlier this year and will be back in the spring to play its part in the circle of life.

Recent rain water is held in storage in one of the new ponds

Wet alder carr downstream of the ponds likewise plays its part in slowing water flow. Here the water struggles to find a good channel to follow. This has been engineered on purpose, but it happens naturally since so many fallen trees and branches lie in its path.

Braiding channel due to fallen logs, branches and leaky dam construction

Eventually however, the stream negotiates its way past the last of the 106 leaky dams in the wood and flows unrestricted as it leaves Wilderness Wood. From now on nothing is likely to stand in its way and it can return to its main job of erosion, transportation and deposition. We have done our job alleviating flooding downstream, all that is required now is for every other landowner within the Ouse catchment to put their own leaky dams in place, to ensure no further flooding can occur.

Either that, or bring back the European Beaver.

The Wilderness Stream leaves the wood carrying away sediment and baring tree roots

Field work is thirsty work for teacher and pupils alike, let’s return to The Barn for a cuppa, before playing our own parts in the water cycle by donating our tea waters to the Wilderness Stream - by way of the toilets.

Follow my exploration of the UK coast on foot and by bike on www.leggingroundbritain.com

David Horne